A Strong Sense of Responsibility as Driving Force

One of the most striking insights of the project has been the strong sense of responsibility people describe when asked about their actions, and how this responsibility often is connected to having experienced or witnessed injustice or oppression themselves.

People are using these challenging experiences as a force to do good and create change, and do so with persistence and a sense of purpose and conviction despite conditions of authoritarianism and war.

While each context is deeply unique, at the same time the similarities between the life stories were also remarkable. We found this strong sense of responsibility across the cases, despite differences in age, gender, social background and geographical location. Empowering turning points and traumatic experiences were seen to have the potential to shape strong and determined, but also humble and empathic, individuals, fighting for a better future for their communities.

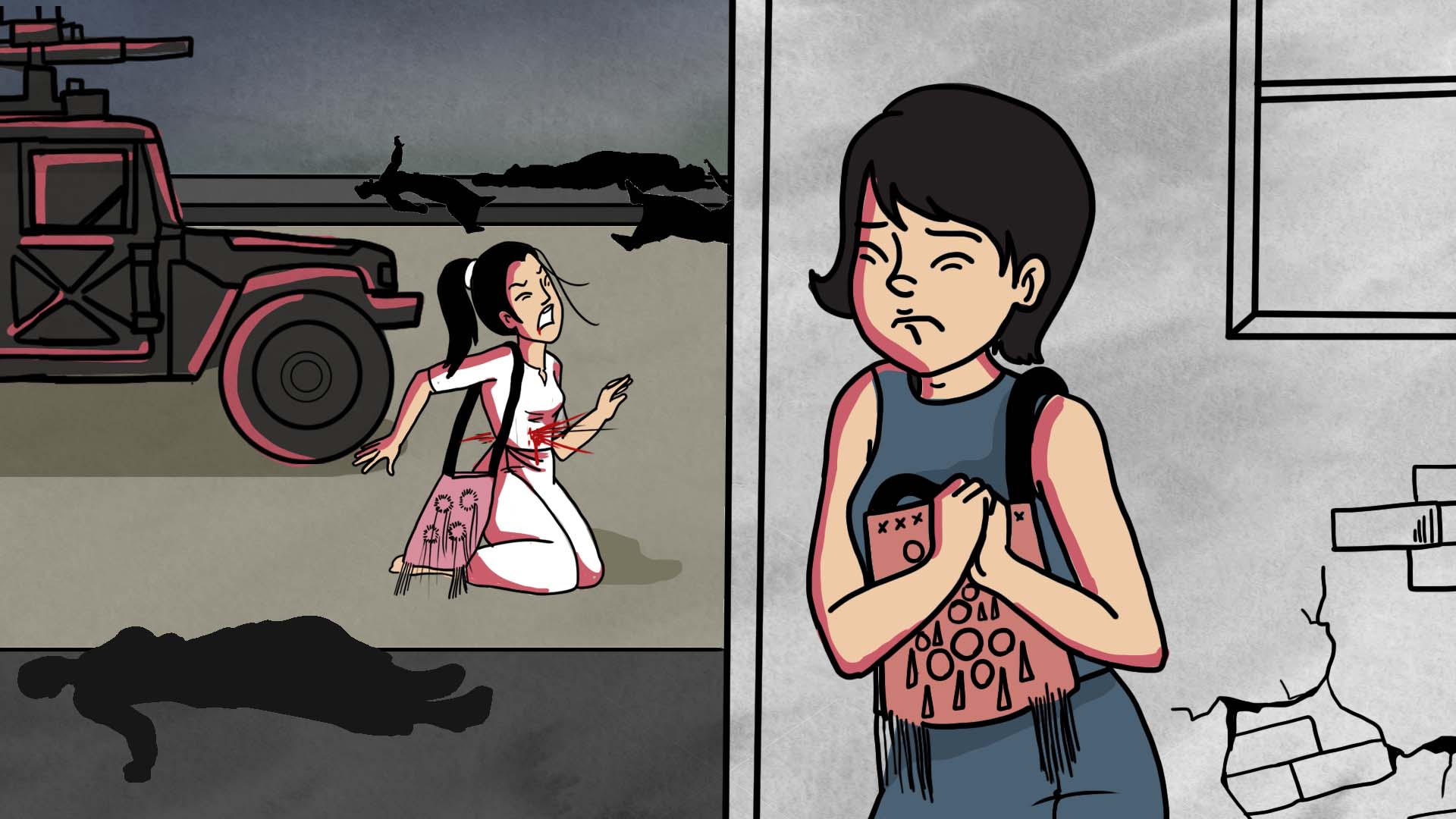

Myanmar

Myanmar’s long history of political persecution and civil war permeated the life stories that we collected.

Lived experiences of violence and oppression are transformative turning points that have triggered the social responsibility of the activists we engaged with.

Our activists have made great personal sacrifices in the struggle for their communities

The research in Myanmar included a case on student activism. In 2015 students in Myanmar engaged in a four-hundred-mile protest march to fight for better education. The movement ended in a violent crackdown, involving the arrests of students, activists, and others. Why did students choose to protest in this context known for violent suppression and imprisonment of protesters? We found that all students described a strong sense of responsibility to take part:

"Since I am doing these things, I can always get arrested and sent to prison. But what happened to me is that I cannot tolerate the injustice. So, when I see injustice, I cannot help but, you know, we need to fight against it. That’s what I believe.”

“So, I think it is my duty. I don't say that I want to become an activist, or I want to become a student activist, or I want to become a politician, I don't say that. But in my mind, I always think that if my country needs me, if something happens, I should participate.”

"Ei Phyu Aung", December 2017 (Stapnes et al. 2020)

Somaliland

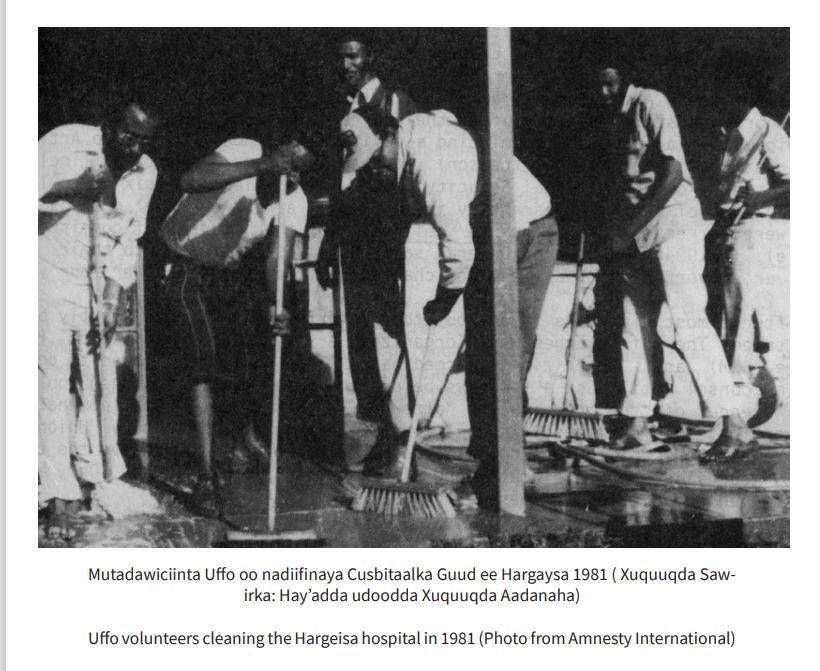

The research in Somaliland focused on a civil resistance initiative from the 1980s known as Uffo, which means “the sweet smelling wind before the rain”.

Doctors, teachers and other professionals came together to address serious negligence in the health and educational sector by restoring a hospital and volunteer teaching. This was both a humanitarian activity responding to the acute suffering of patients, and a way of resisting the oppressive policies of the regime while navigating the high risks in an authoritarian setting.

They wanted to illuminate the government's neglect of its duties, and show their community that they could take matters into their own hands. They further wanted to mobilize people across clans to counter the regime’s repressive split and rule tactic, inherited from previous colonial rule.

Photo of the commemoration site of the Uffo protests, Hargeisa

Photo of the commemoration site of the Uffo protests, Hargeisa

When the professionals were arrested a few months later and risked execution, this became the spark that ignited and inspired secondary school students to protest the regime openly. This was the first open street protest against the Siad Barre regime. Due to these reactions, the regime commuted the death sentences to prison sentences. The resistance continued and eventually led to the self-proclamation of Somaliland in 1991.

Hence, these events represent a key transformative moment in Somaliland’s’ history and thereby provide an opportunity to study individual and collective mobilization that drive societal transformation. The Uffo professionals described a strong sense of care for the community and responsibility to address injustice. You can read the whole story in both English and Somali here.

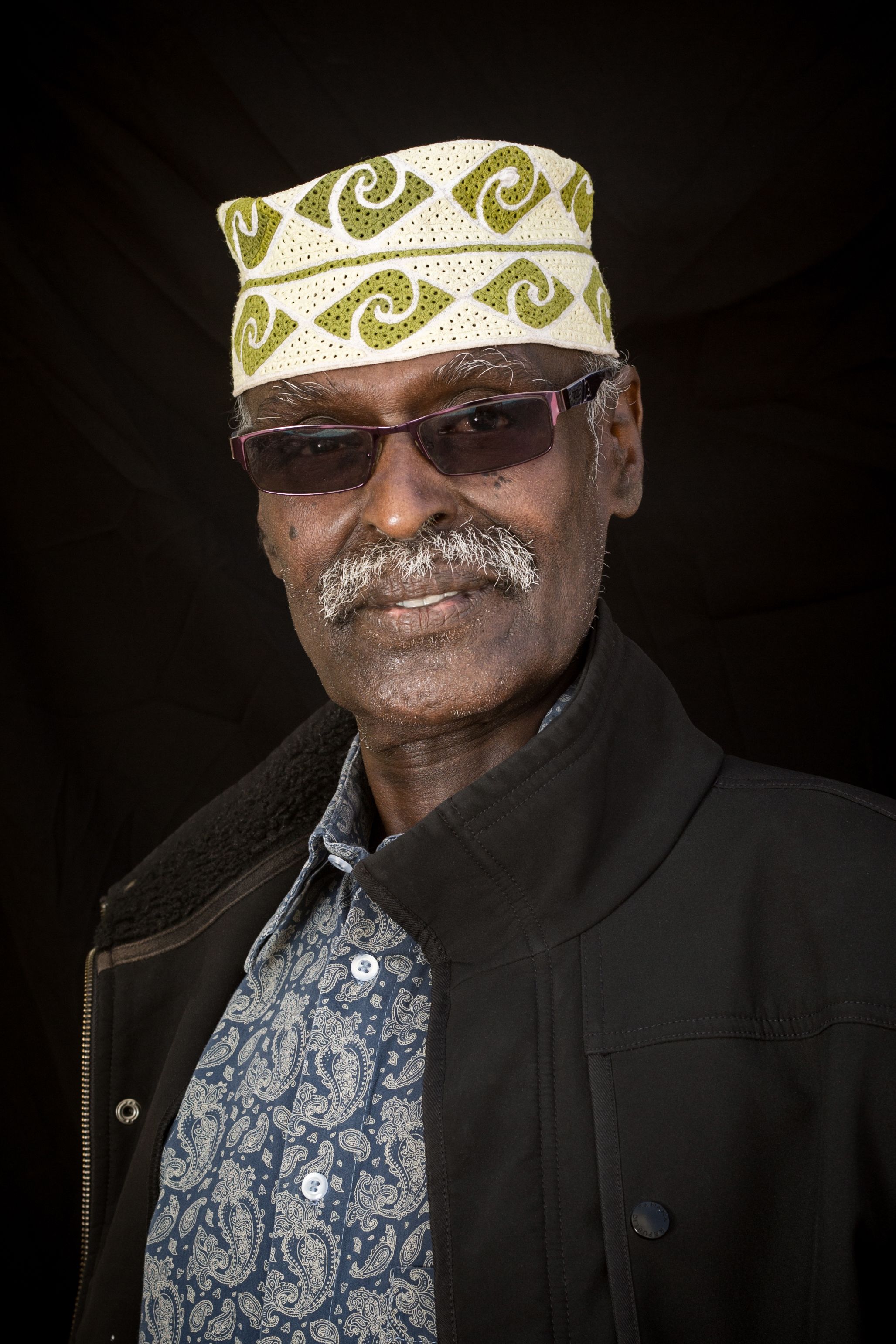

Fighting for justice. That was the greatest motivation […] There is something that you live for and you have to do before everything else… to fulfill the responsibility. Human beings have feelings and ambitions that are far more important than just living for yourself and earning your living […] We don't regret it, because a human being has to live for ideals larger than himself.

Dr. Mohamud Sheikh Hassan Tani. Photo by Mustafa Saeed

Dr. Mohamud Sheikh Hassan Tani. Photo by Mustafa Saeed

"I won’t regret what I have done. Because the wisdom says that the greatest crime a person can do is indifference to injustice".

- Dr. Mohamud Sheikh Hassan Tani, Hargeisa, December 2018

"There was a lot of injustice to the patients of the hospital and the government neglected it".

- Dr. Mohamud Sheikh Hassan Tani, Hargeisa, December 2018

Syria

"There was a big group of kids that were absent from school. They are our responsibility."

- A future for Syria (animation)

In Syria, we asked about the motivation of civil society activists who dedicated themselves to education in the civil war, at the cost of their own safety. We found that feelings of responsibility went in pair with the activists’ beliefs that they could make a difference. For example, one young teacher related that he felt personally responsible for helping the children who lost access to schooling when the war broke out. He perceived that leaving the country would be shameful because he had competency to help:

"I had a strong feeling that these children were my destiny, that I would be held accountable for them on Judgement Day. I could not leave them. They were children. There were armed groups and the regime and they could fight each other to hell. My responsibility was to not leave these children alone".

“Adam”, June 2018 (Selvik 2021)

"[...] you say shame on a young man when he can help with civil work. There is a war and you are able. If you leave it means you are fleeing. You are fleeing from a responsibility. You saw the civilians and the old people; how come you left them?"

“Adam”, June 2018 (Selvik 2021)