Collecting Life Stories

The TRANSFORM project has collected and highlighted the stories of people who attempt to challenge injustices in contexts of violent conflict and repression.

This was done through meetings and long conversations with many ordinary – and at the same time unique – engaged individuals.

The conversations showcased their sense of dignity, acts of care for others, and courageous ability to stand their ground in the face of repression.

Even under conditions of war and oppression, some people manage to get together with likeminded others and employ their limited resources to resist.

These personal stories are often not the ones we think about or hear about in relation to conflict contexts. Learning about the experiences, hopes, dreams, and worries of people who resist such circumstances gives us a wealth of information and insight that can help us develop a fuller understanding of what is going on in these settings. Such insights have the potential to nuance conventional images of ordinary people’s lived experiences in conflict contexts.

"I had met many of the people I interviewed before, and even interviewed them, but the focus on their life history opened up multiple doors to more profoundly understand the motivation of these people, as well as the country and the political struggles that they navigate in.

The most inspiring experience for me was how much more I learned about the people that I interviewed, and about their political purpose and drive, when I talked to them about the story of their lives, rather than about specific political issues".

Visual storytelling

When the research in Somaliland, Myanmar and Syria (carried out in Lebanon, Turkey and online) was well on its way and the researchers had a clear sense of key findings and most interesting stories, we started the process of creating comics and animations. A team from positivenegatives went along on fieldwork in Somaliland and Myanmar to discuss the existing material, conduct additional interviews, and meet with those whose stories we would tell visually.

Interviewing Da Bawk Ja at her home/office in Myitkyina, Myanmar. January 2019

Interviewing Da Bawk Ja at her home/office in Myitkyina, Myanmar. January 2019

Once we had decided on the stories, we worked with a script writer to adapt interview transcripts for the animation or comic format. It was important for us as a research team that the ‘fictionalised’ script reflected the lived experience of those whose stories we told, so we worked closely with the individuals involved.

After the scripts had been approved we translated them into Burmese, Arabic and Somali and once again shared these with the individuals whose stories were being told, as details and nuance can sometimes be lost in the translation process.

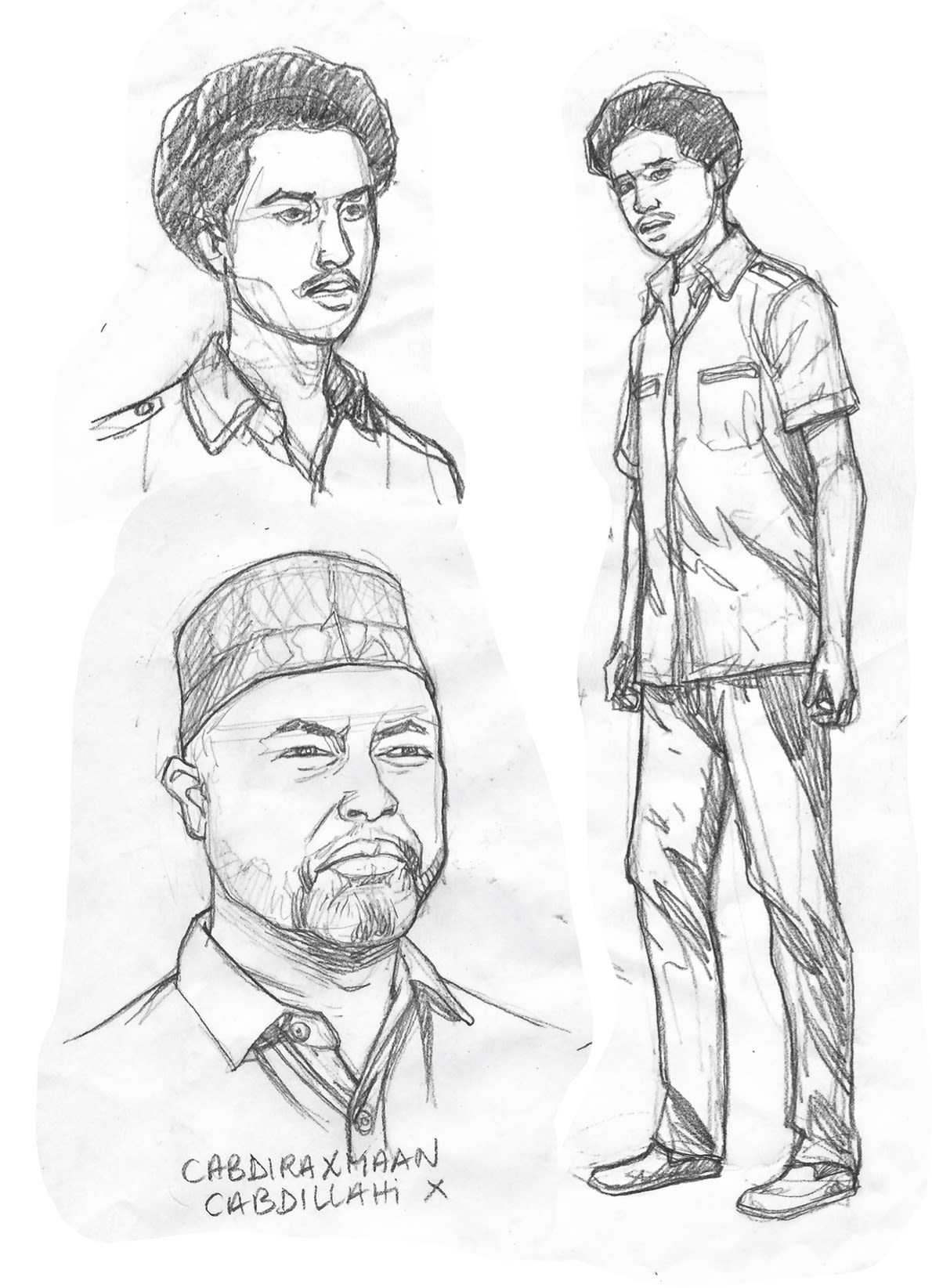

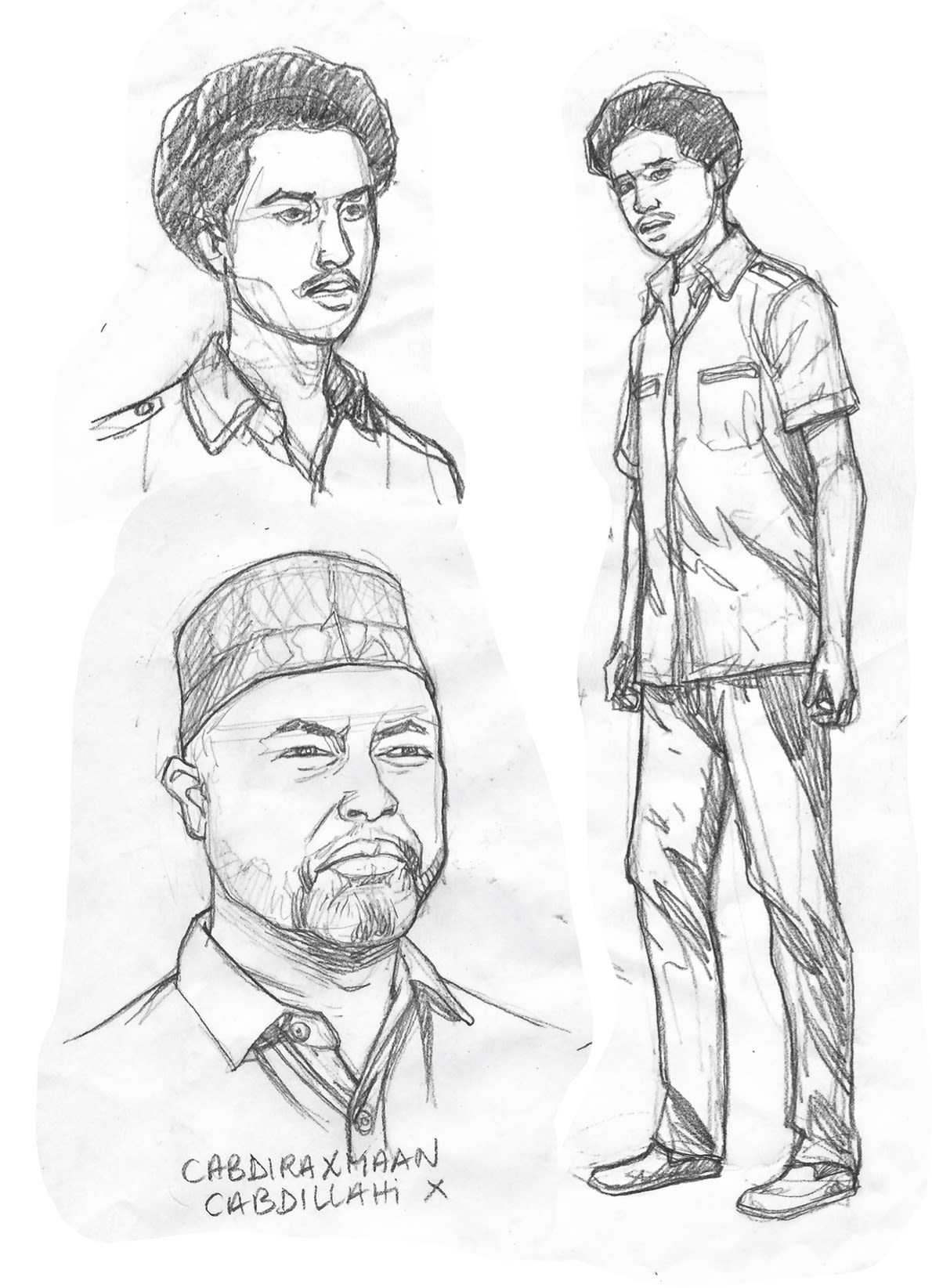

The next stage in the visual development process was identifying artists for each of the stories.

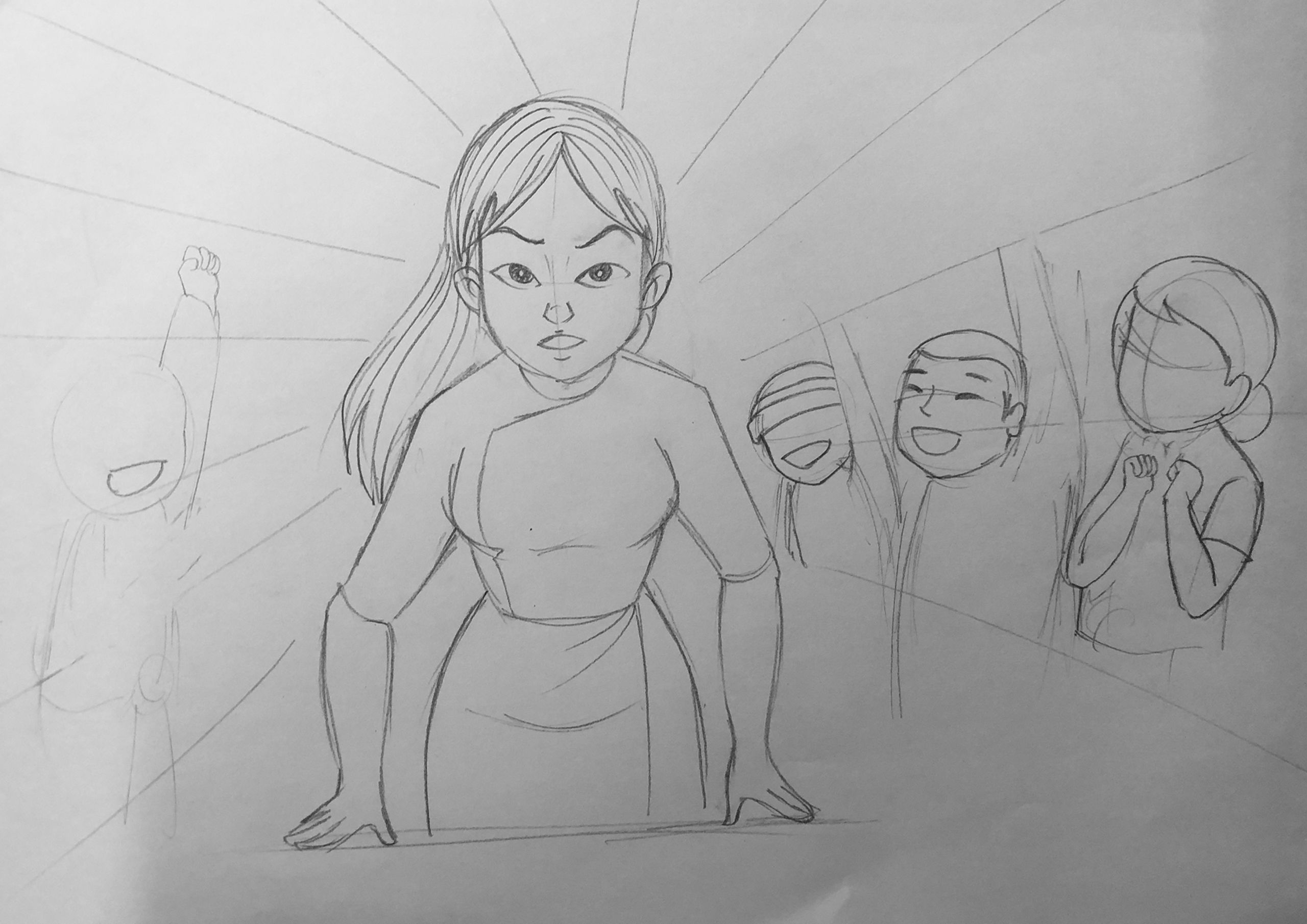

In Myanmar we worked with Kue Cool, a young, female artist who joined us in Myitkyina for the second interview with the woman whose story we were telling. Kue Cool heard the story first-hand during that visit, which helped her greatly in her work on the animation.

For Somaliland we worked with established Congolese artist, Pat Masioni.

Pat remembered learning about the Somali conflict as he grew up in the DR Congo and felt it an honour to illustrate the story of the UFFO Group that had inspired him.

His 1980s comics style was a great fit for the story he was telling.

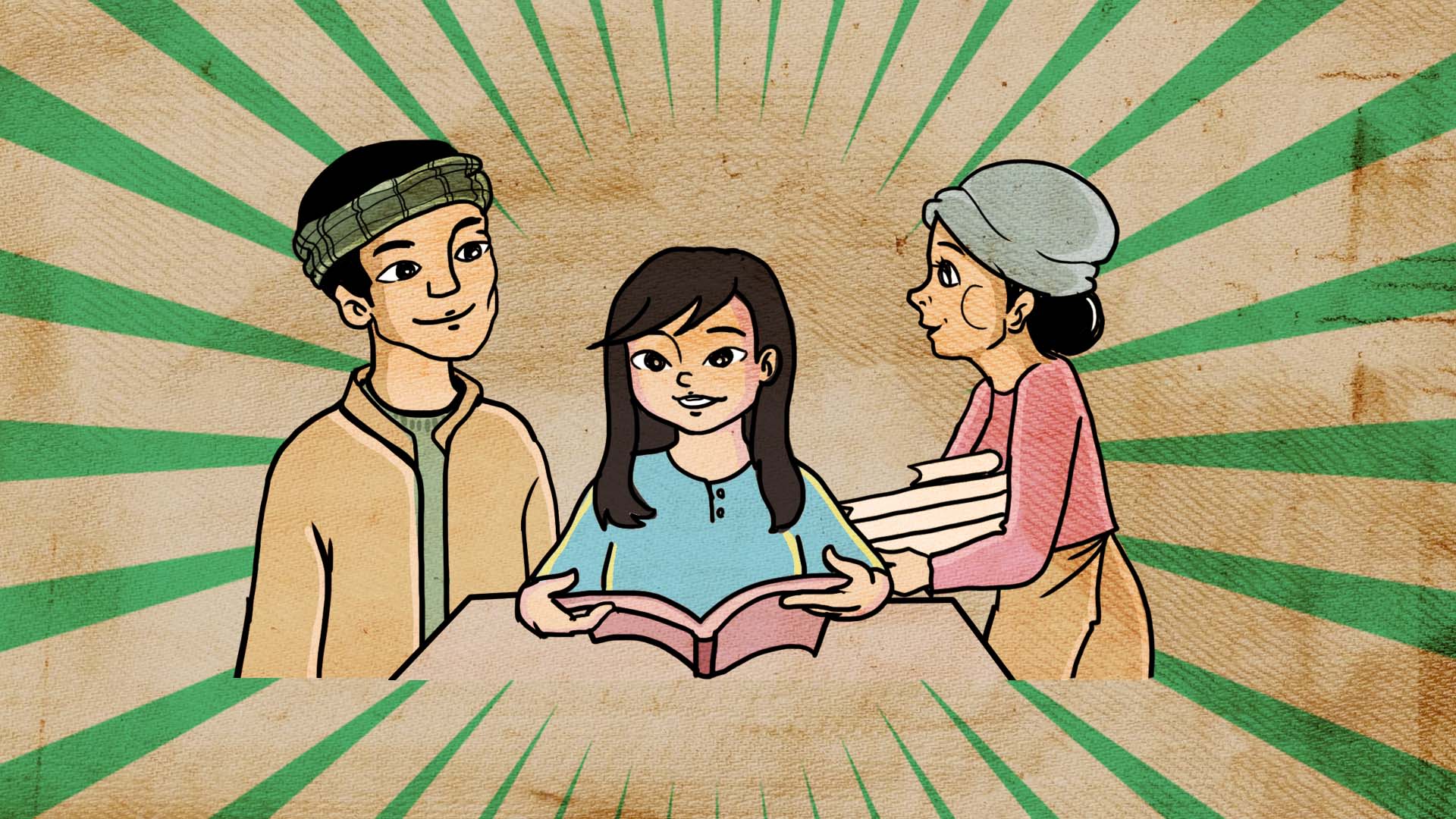

Syrian artist Diala Brisly created the animation 'A future for Syria'. Her beautiful style of illustration and animation, combined with her personal experiences that matched the story she was asked to visualize, made Diala a perfect match for the project. Diala did not just participate in the project as an artist, but was also interviewed and participated in a public seminar.

Once the character sketches were approved by the protagonists we could move into the storyboarding stage with the artists.

We gathered visual material to help the artists with their visual references and at every stage we sent the storyboard sketches to the individuals whose stories were being told for feedback.

The artists understood the importance of not just getting the story right but also the visual details of the environment, clothes, and facial expressions. After many rounds of feedback, the storyboards were approved and the artists finalized their artistic work.

The process of creating animations and comics based on the research has been even more valuable than we had imagined beforehand, teaching the research team how effective and powerful it can be to communicate complex and difficult stories visually.

The research team was impressed to see how an artist would approach a story, and how this different – audio-visual – approach would bring out new elements and details, enriching the story and its societal importance.

Researchers, respondents and artists took great care and responsibility for their work and the stories being told.

Throughout the project, the researchers on the team have had to think closely about their own position as researchers and about how to represent the stories of others; in dialogue with everyone involved in the storytelling. On this journey, working audio-visually provided a new way of approximating people’s experiences.